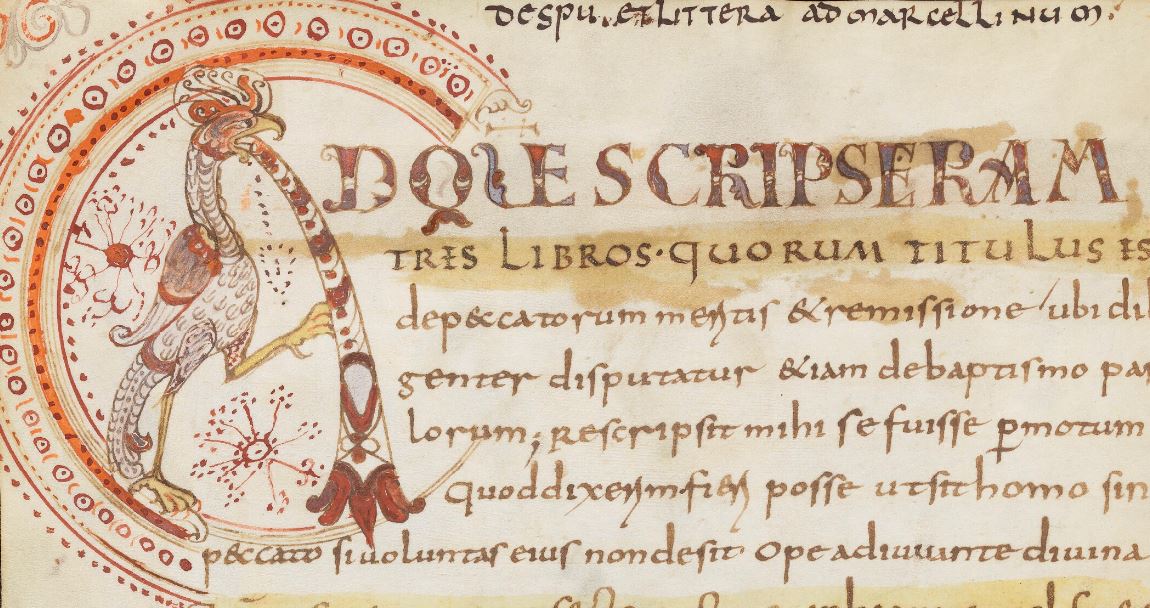

I will admit to a moment of panic last week when MS. Laud Misc. 134 showed up among the newly digitized manuscripts on this site. That initial A–made up partly of a bird, its left leg outstretched to form the crossbar–looked too familiar. Had I seen it before? Had we accidentally photographed the same manuscript twice?

We had not, thankfully. In the last few months, the Bodleian’s new Polonsky cataloguer, Tuija Ainonen, has been working through the backlog of photographed Würzburg manuscripts, converting the entries in Daniela Mairhofer’s 2014 catalogue to electronic TEI records. The result is that while MS. Laud Misc. 134 went online just last week, it was photographed over a year ago. The initial A is familiar to me because we used it as a placeholder image when we were designing this website. It was one of the first Polonsky German manuscript images I saw, and it established the character of the collection in my mind.

Now, a year and 89 digitized manuscripts later, there is no denying that MS. Laud Misc. 134 is an unusual manuscript within this project. Most of its peers are sadly lacking in birds, for one thing. It’s on the old side, as well; it’s one of a dozen digitized 9th-century manuscripts from the Cathedral Church of St Kilian in Würzburg, each written in a beautiful Carolingian minuscule hand. As with every manuscript, of course, the more you look, the more interesting things you find.

Scratched-out words

Medieval scribes are often pictured with a pen in one hand and a knife in the other, ready to scrape away mistakes as they work. I have never actually noticed a scrape mark in a manuscript before, but the marks in MS. Laud Misc. 134 are especially obvious, not least because they have not been written over. They appear to have been made after the writing of the manuscript was finished.

In another Würzburg manuscript, MS. Laud Misc. 135, scratched-out letters have been written over by a later hand.

Quire signatures

In part 2 of the manuscript, the end of each quire is marked with a Roman numeral inside a large coloured circle. There are twelve quire signatures, corresponding neatly with the gatherings visible in the head and tail images of the manuscript. Quire signatures are not uncommon in medieval manuscripts, but they are usually undecorated numbers, as in MS. Laud Misc. 122. The ones in MS. Laud Misc. 134 are exceptionally beautiful, although they have sadly been slightly trimmed during a rebinding of the manuscript.

Tail of manuscript.

Initials

In addition to the ten-line bird initial A, with its circular border that appears to sit just behind the main text, there are smaller coloured initials throughout the manuscript, including an N decorated with interlocking blue and red loops on fol. 48v. Adjacent to a large initial P on fol. 89v, the explict and incipit are highlighted in red and sandwiched between sparkling red and gold bands. (Fol. 89v also happens to be the end of quire 10.)

Incipit, explicit and initial P, fol. 89v.

19th-century notes on dating

One of the reasons we credit cataloguers in our digital facsimile metadata is that very little of what we know about these manuscripts is set in stone, and interpretations may differ from one scholar to another. In this case, evidence of a lively conversation about the dating of the manuscript is preserved on the flyleaves. On the inside upper board, a note in pencil reads, “Mr. J.W. Bradley thinks this is 8th cent”. This would have been John William Bradley, author of the 1905 book Illuminated Manuscripts. Underneath, there is a note dated 1899 from E.W.B. Nicholson, Bodley’s Librarian from 1882-1912. He writes that Bradley’s assertion was written before 1890, and goes on to say, “I am now quite satisfied that this is a 9th cent. MS., and not a late one either…and that it belonged to St Kylians, Würzburg.”

Notes on the inside upper board.

Another piece of the story appears on the next image. Fol. i of the manuscript is a pasted-in note, written in 1889 by Sir Edmund Maunde Thompson, the principal librarian of the British Museum. (The note is written on stationery embossed with the British Museum’s crest.) It reads, “I think Coxe is not far out; but it may be 9th. 8th is quite absurd”.

Underneath Thompson’s note, Nicholson explains that it was written after seeing reduced photos of fols. 15v and 89v. The “Coxe” Thompson refers to would have been H. O. Coxe, author of the Quarto Catalogue published in Latin in several volumes between 1858 and 1885, which tentatively dates the manuscript to the early 10th century. It appears, then, that prior to 1890, experts variously dated the manuscript to the 8th and early 10th centuries, and by 1899 Bodley’s Librarian, at least, was confident in dating it to the first half of the 9th century. Things have changed very little since then, as far as the dating of this particular manuscript is concerned. The Bodleian’s digitized copy of the 1969 reprint of Coxe contains a handwritten correction changing “sec. x forsan ineuntis” to “sec. ix”, and in her 2014 catalogue of the Bodleian’s Würzburg manuscripts, Daniela Mairhofer dates the manuscript to the second quarter of the 9th century. Mairhofer’s date is the one we’ve published alongside the digital facsimile of the manuscript for this project.

Emma Stanford is the Bodleian’s Digital Curator and the project manager for Manuscripts from German-Speaking Lands.

Additional Reading

Daniela Mairhofer, Medieval Manuscripts from Würzburg in the Bodleian Library, Oxford: A Descriptive Catalogue (Oxford, 2014).