The second step on a manuscript’s digitization journey is assessment. Selection naturally comes first - you can read about the Bodleian’s collections of manuscripts from German speaking lands here - but before photography can commence, volumes are assessed for suitability. For a project of this scale, this means a photographer and a manuscript curator heading down to the stacks once or twice a month, list in hand (and occasionally a lucky digital curator in tow). One by one, grey conservation boxes are retrieved from their shelves, opened up, and the manuscript carefully examined. Each is checked to ensure it can be photographed safely or if conservation might be required; they’re then assessed for how challenging photography might be.

Bindings are checked first. Though often not contemporary to the rest of the manuscript, they can be several centuries old. Most of the Bodleian manuscripts digitized so far in the project were part of the collection of Archbishop William Laud, Chancellor of Oxford University from 1630 to 1641. These were rebound in the 1630s, so the bindings have been in use for getting on four centuries. Many are holding up well, or have already had work done to ensure their stability; but others are weakening, and need intervention from conservators prior to photography. Our Head of Book Conservation wrote previously on this blog about an especially involved piece of binding conservation work on a Laud manuscript chosen for this project. Appearances can be deceiving here: it’s not always the case that damaged bindings make a manuscript unsuitable for photography, so long as there’s no risk that further damage could be caused. We wrote about working with damaged bindings earlier in the year.

If the binding seems stable enough for safe photography, the curator and photographer then carefully page through the manuscript. They’re looking in part for further risks of damage, such as loose or fragile leaves which might need conservation work, or need handling with even greater care than normal. But the photographer is also trying to get a sense of how straightforward or otherwise photography will be. The simplest factor to assess is the angle of opening; that is, can the manuscript be (safely) held open wide enough for a camera to get an unobstructed view of each page. Narrower angles mean more time must be spent preparing each opening for photography and fine-tuning depth-of-field, and as a rule of thumb, opening angles below 45 degrees are very challenging indeed to shoot.

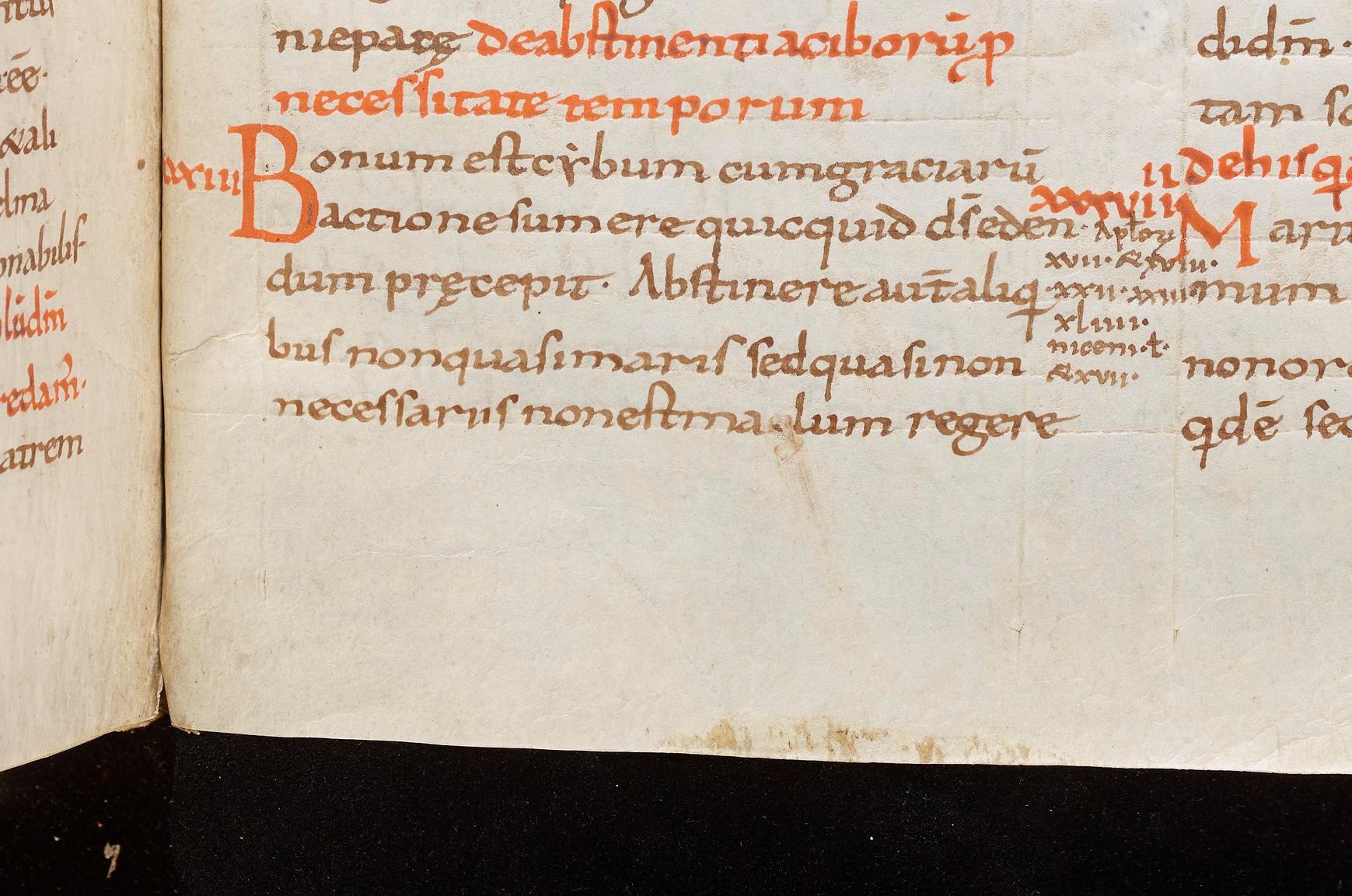

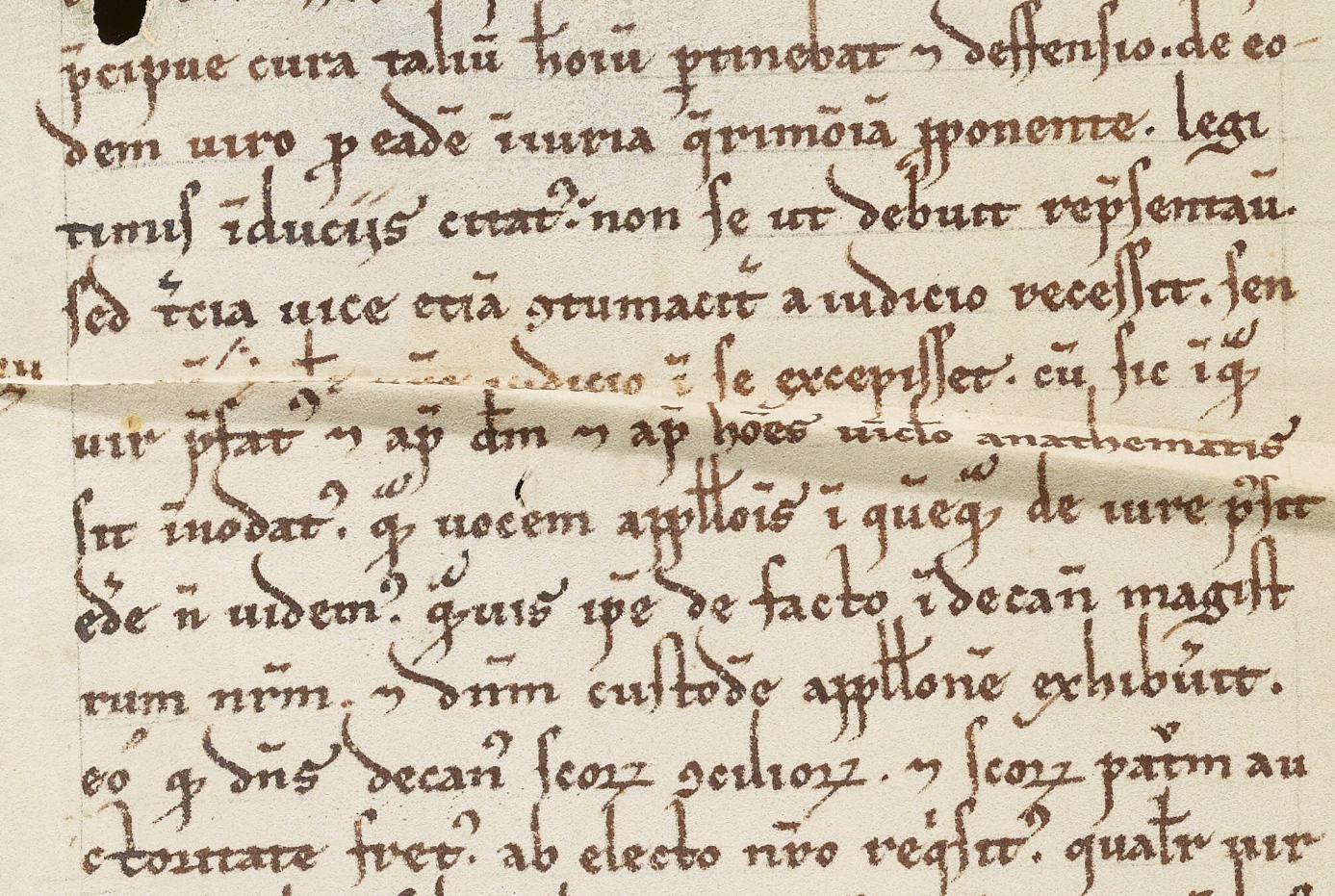

The next check is for how tightly into the gutter text is written. Even if the angle of opening is enough for an unobstructed view of the page, tight bindings or narrow margins can mean text curves into the gutter. In extreme cases there can be text loss even for someone reading by the naked eye; but even where the beginnings and ends of lines haven’t been completely obscured, they can run tight enough into the binding that text is lost when photographed from a flat angle. The degree to which text runs into the gutter will vary throughout a manuscript, depending on how it’s been bound, and according to variations in the size of the margins left in different writing campaigns.

A very tight binding, narrow margins, and small script made it a challenge to capture text near the gutter in MS. Laud Lat. 3.

As well as the nature of the binding, the material used for leaves can affect the ease of photography. While paper is less sturdy than parchment, it tends to open a little more easily, allowing for wider opening angles and less tight gutters. The material can also affect how warped or distorted leaves get, with parchment more susceptible to this. The challenge to the photographer here is ensuring light falls evenly across the page. Fluctuations in the surface can cause light to pool in certain areas, or create slight shadow in others. This can be accommodated by adjusting the location and angle of light sources, or by adjusting how the pages are held in the photography cradle, but this adds to the time needed for photography. Very warped pages can also prove awkward when tuning the depth-of-field of a shot.

Taken together, the ease of opening, possibility of text loss, and irregularities in the leaves are used to predict how much time will be needed for photographing the manuscript. This helps with project planning, and gives an advance warning for the photography team of any particularly tricky manuscripts. Very rarely, the difficult decision might be made to deselect a manuscript from the project altogether, even if it’s safe for handling. This is the case where the binding is simply too tight to make photography practicable, or if there is likely to be significant loss of text in photography throughout a manuscript; sometimes it’s deemed more worthwhile to spend our resources on a manuscript which can be shot without text loss. Happily, very few manuscripts have so far had to be passed over in this project.

For more on photography in this project, see John Barrett’s post on photographing bindings.

Tim Dungate is the Bodleian’s Assistant Digital Curator.

Manuscripts featured in this post: