This summer our photo department began digitising manuscripts from one of the six main monastic houses which had made their way into the collections of the Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel: the books from the high medieval Benedictine abbey of Lamspringe near Hildesheim. Among all the manuscripts that were copied by the hands of men, we can now present books written and decorated by female hands, which is only one aspect making the Lamspringe collection with its 23 exemplars extraordinary. This medieval corpus offers beautiful decoration and illumination not only from an art historical perspective and thus forms an appealing group of illuminated manuscripts. From the 23 Lamspringe codices we selected 16 exemplars (Cod. Guelf. 204, 443*, 447*, 475, 480*, 510*, 511*, 519*, 718*, 903*, 905, 943*, 997, 1012*, 1030*, and 1113* Helmst.) on which this article seeks to shed light regarding their features as a group of manuscripts. Twelve of these (asterisked above) can already be explored here online.

Formerly founded as a house of canonesses – a rather secular and therefore more liberal model of a religious community – around 850 by Count Ricdag and his wife Emhild in the south of the Diocese of Hildesheim, the convent was reformed to a Benedictine abbey just before 1130. From then on the abbey was religiously, economically, and politically shaped and controlled by the bishops of Hildesheim. The Benedictine abbey of Lamspringe was one of the wealthiest and most well-equipped convents in Lower-Saxony throughout the 14th century. Its library’s corpus of 23 codices, three of which with liturgical contents, not only illustrates their female scribes’ and illuminators’ level of theological education and the fact that their daily routine can easily be compared to the religious life of their male equivalents, on whom still more research has been done so far. It also shows once more that the institution of the abbey goes hand in hand with the scriptorium (Lat. scribere – ‘(to) write’) - and with a library which collects, provides, and preserves the writings created by the hands of monastics.

Before paper became the number one writing medium in Europe with the advent of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press around 1450, people had relied on the more robust qualities of parchment. Parchment production was a complex process and implied physical labour: After having been soaked in water and dehaired, the animal membrane was fixed into a stretching frame, then scratched, scraped, and finally treated with powders and pastes of calcium compounds such as chalk in order to avoid the running of ink and colours in the writing process. In German-speaking lands, cow skin, or in some cases sheep skin, was used predominantly for parchment. The neatly cut and folded sheets of parchment were sewn together forming so-called quires; then ruled, inscribed, and ultimately bound into a manuscript.

Ganzseitige Miniatur eines Schreibers an seinem Pult, der seine Schreibfeder schärft, bevor er den Text auf das bereits linierte Doppelblatt kopiert (Cod. Guelf. 1030 Helmst., fol. 1v, 1151–1175)

Scribe, rubricator, and illuminator (the one responsible for the manuscript’s illustration through decorated initials and every other ornament) could be one and the same person. The scribes usually left spaces for initials and miniatures on the parchment while copying the text from the exemplar onto the parchment leaves, the illustrators however frequently overlooked the gaps and left those spaces blank. Beside the considerable number of scribes, 28 in all, who can be distinguished for the time period between 1170 and 1204. we even know the names of two female scribes: Odelgarde and Ermengarde. A colophon (a short comment added by the scribe, usually at the end of their scribal work) tells us about a third scriptrix. Judging from the style, their type of script is to be classified in the transition period from the (late) Carolingian minuscule to an early form of Gothic script (Proto-Gothic) with which its whole aspect becomes less rounded, characters appear more angular and pointed, and the space between the letters within a word diminishes noticeably.

The Benedictine nuns of Lamspringe worked diligently and created books in which their passion for ornamental detail becomes visible. Their parchment codices feature numerous larger zoomorphic and figurative initials, trailing in (fanciful) heads and bodies of animals or floral ornaments.

, fol. 2r, 1176–1200](/img/blog/30-2.jpg)

The vertical strokes and ends of initials are frequently decorated with half-palmettes. The tails of the Q-initials are repeatedly depicted as bodies of dragons spitting leaf tendrils and/or whose tails trail in floral tendrils as we can see it in 510 Helmst. (fol. 119r, 133r, cf. A-initial with dragon and lion on fol. 52v), 519 Helmst. (fol. 1v, cf. floral ornaments in F- and P-initials on fol. 22r and 77v) and also brightly coloured on fol. 26r in 443 Helmst.

, fol. 133r, 1151–1175)](/img/blog/30-3.jpg)

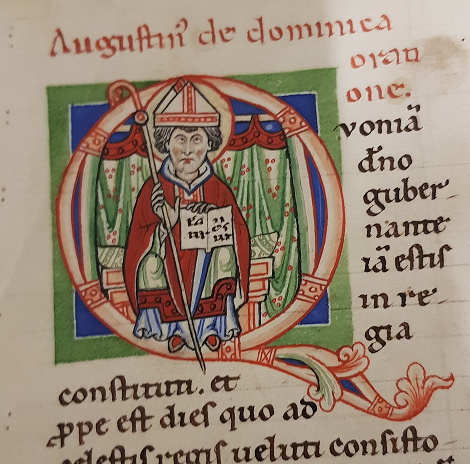

Red, green, and blue dominate in the range of colours in the Lamspringe manuscripts which is evident in the figurative depiction of St Augustine (354–430) on fol. 3v in 204 Helmst.: Sitting enthroned while attired in mitre and crosier, he is presenting the opened double page (Lat. bifolium) containing the Pater noster to his readership. Both the church father’s vestment and the curtain behind him are artistically applied with arrangement of the folds, the latter of which is even decorated with a red three point pattern.

, fol. 75v, beginning of 4th quarter of 12th century)](/img/blog/30-5.jpg)

The portrayal of Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) on fol. 75v (903 Helmst.) in the bow of the P-initial is reminiscent of the Q-initial encircling St Augustine. With regards to both style and colours, the initials greatly resemble each other and may well have been painted by the same illustrator - and the text may well have been written by the same scribe whose hand we see in 204 Helmst. judging from the aspect of the script. In fact, the manuscripts illustrated and illuminated by the nuns of Lamspringe are part of a current cataloguing project involving the illuminated manuscripts preserved at the Herzog August Bibliothek.

It is now time to strike a blow for the nuns of the high medieval Benedictine abbey of Lamspringe who maintained a highly efficient scriptorium. In the course of the Reformation monasteries and their libraries were dissolved, and oftentimes information about when and where which books travelled and even disappeared is rare or simply not at hand still. However, in the case of the Lamspringe manuscripts it is thanks to Duke Julius of Brunswick-Lüneburg who incorporated the corpus of 23 codices into his collection in his princely court in Wolfenbüttel in 1572. This is why these books bound, copied, and decorated by religious artists have survived the times and can thus be explored further today.

By Irina Rau

Further reading:

Helmar Härtel (ed.), Geschrieben und gemalt. Gelehrte Bücher aus Frauenhand: Eine Klosterbibliothek sächsischer Benediktinerinnen des 12. Jahrhunderts (Wolfenbütteler Ausstellungskatalog 86), Wolfenbüttel: Herzog August Bibliothek 2006.

— "Gelehrte Bräute Christi. Zur Umstrukturierung der Frauenklöster im Hochmittelalter: Ein neues Ideal geistig-geistlichen Lebens," in: Die gelehrten Bräute Christi. Geistesleben und Bücher der Nonnen im Mittelalter, ed. by Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer (Wolfenbütteler Hefte 22), Wolfenbüttel / Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2008, 7–13.