An internet wag has observed that one will emerge from Covid-19 isolation as a monk, a hunk, a chunk, or a drunk. I have settled on the first course. The Christmas before the pandemic began, my children gave me a sketchbook and a set of coloured pencils. Their timing was providential.

Shaping psalters, past and present

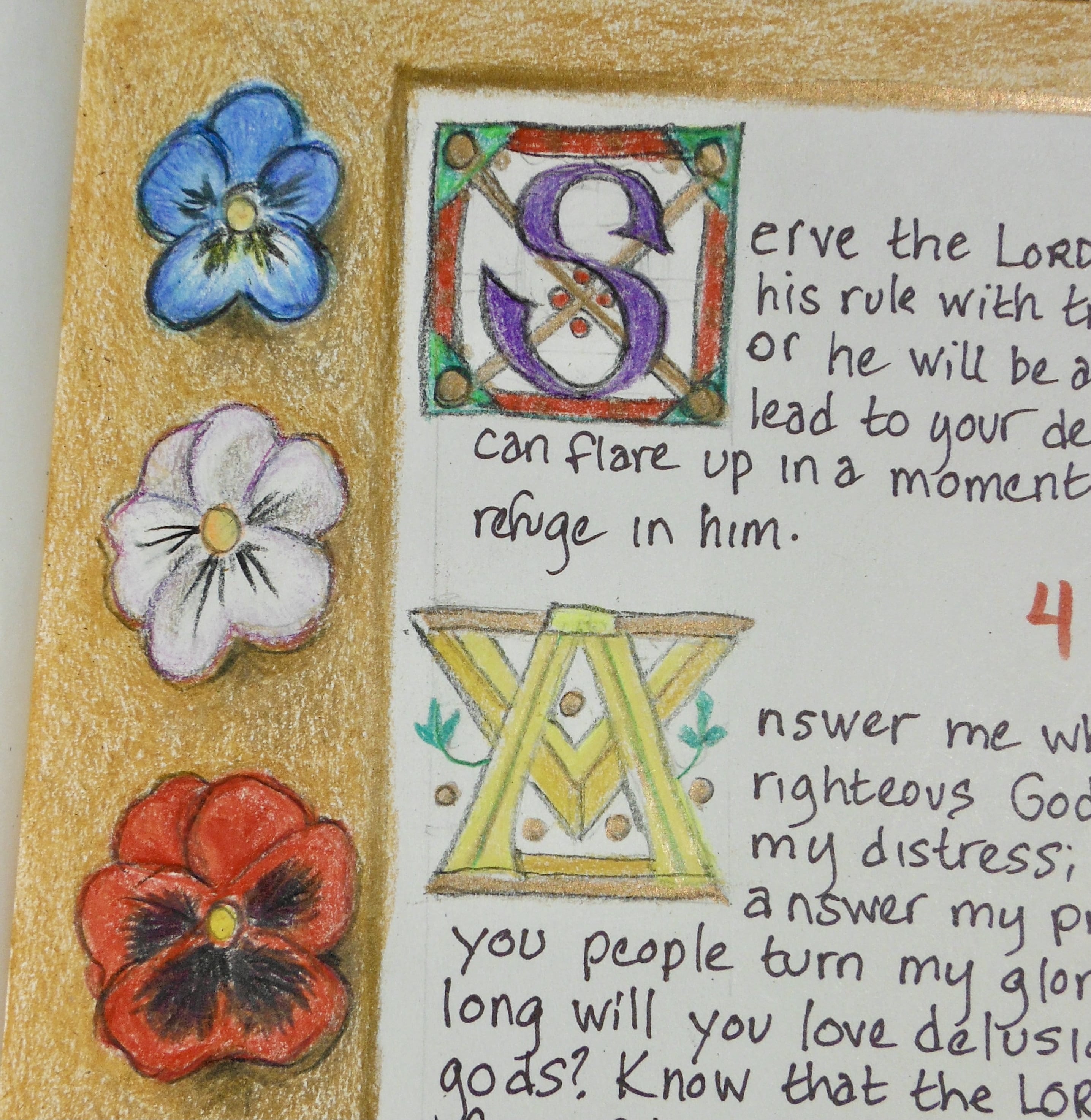

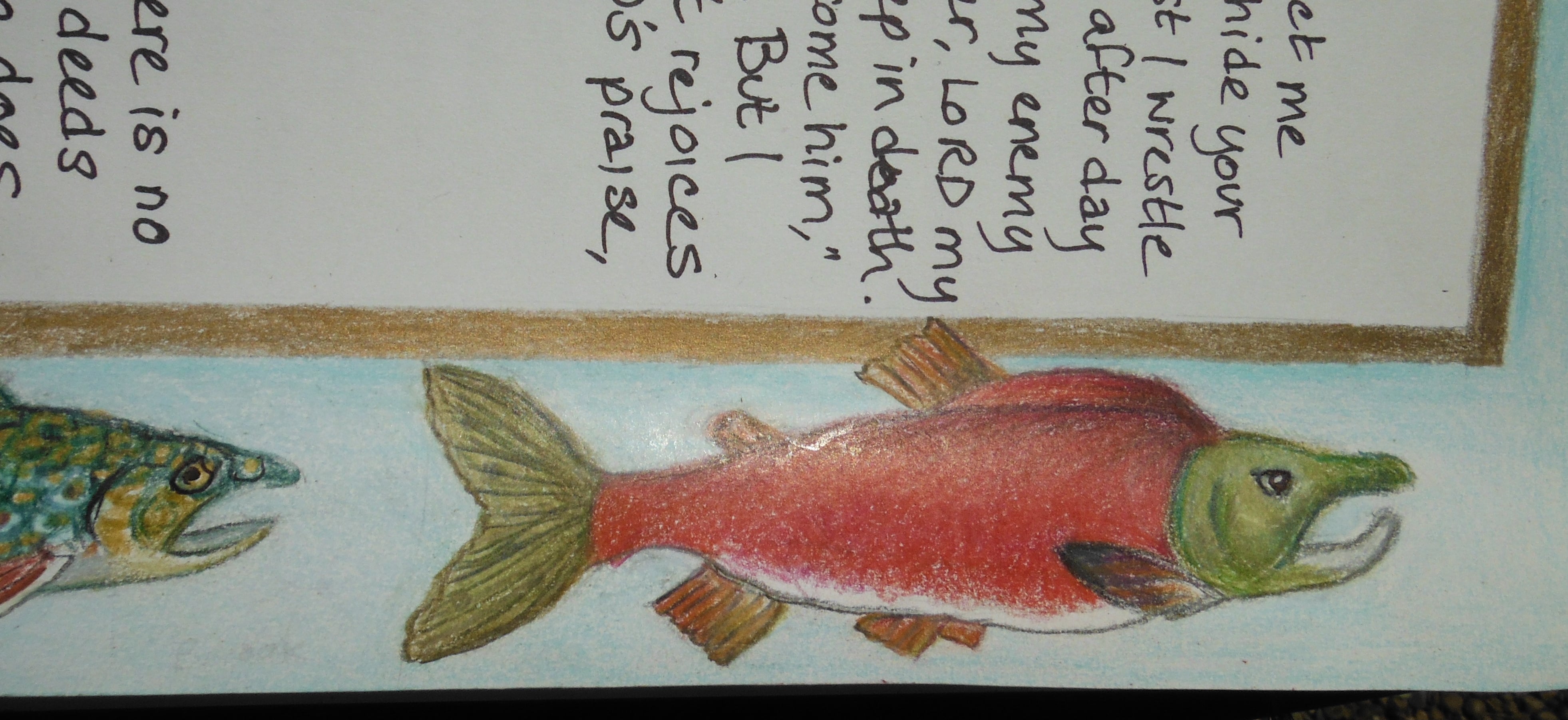

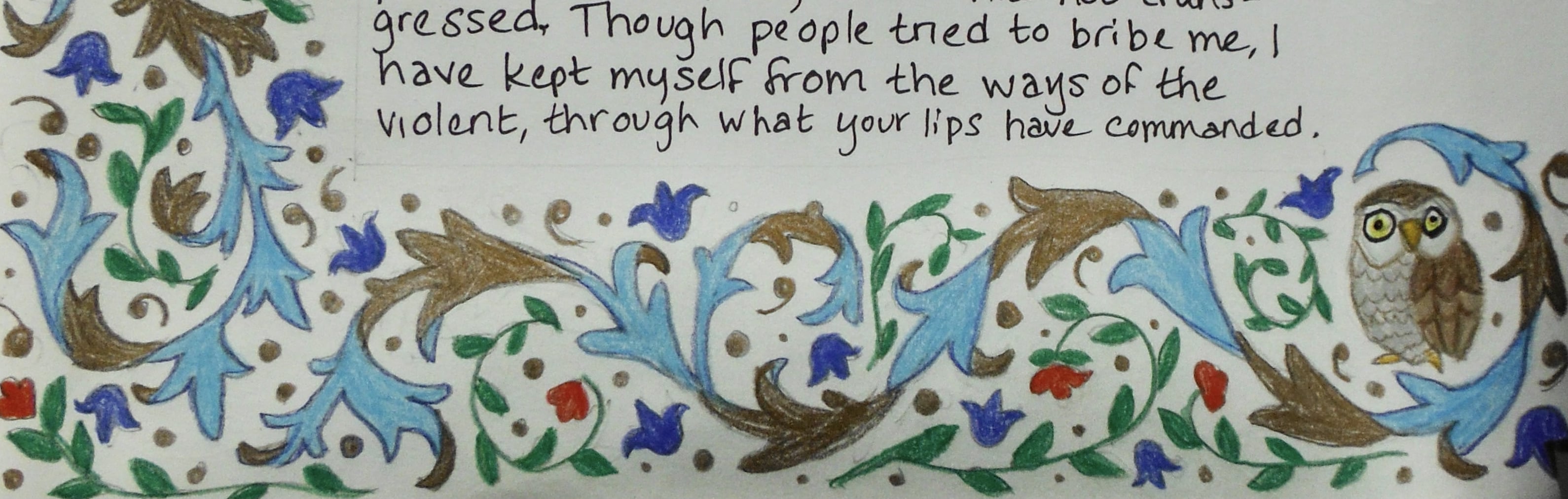

Since March 2020, I have been sheltering intermittently at home, which has provided me with the opportunity to create an illustrated psalter. In doing so, I feel an immediate affinity for a Cistercian nun, Margaret Hopes, who created her own psalter half a millennium ago. This book is now in the Bodleian Library: MS. Don. e. 248.

A youthful King David and Bernard of Clairvaux in the psalter of Margaret Hopes: Bodl. MS. Don. e. 248, fol. 20v.

Margaret lived in the Abbey of Medingen in Lower Saxony before the Reformation. There are certainly differences between us, as I am a teacher in the state of Oregon.

Margaret’s parchment prayer book is diminutive and fits in the palm of one’s hand at 105 × 78 mm. My sketchbook dwarfs it by contrast, at 360 × 280 mm, with large acid-free paper pages. It only accepts dry media, so my gold pencil is unable to duplicate the glowing illumination of her psalter’s gold leaf. Her illustrations are limited to a handful of bright hues, while I have 150 different colours that can be blended in countless ways. Margaret writes a rigorous Gothic hand, while I have chosen a modern script. All these differences are no barrier to taking inspiration from Margaret’s work.

Digitized books for inspiration

One of the greatest contrasts between Margaret and myself is immediate access to countless digitized images of manuscripts online and in printed collections. I am finding inspiration for the borders of my pages in Winheid von Winsen’s Easter book, the Hours of Mary of Burgundy, the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, the Hastings Hours, the Isabella Breviary, and others. I admire the incredible scrollwork and attention to the details of natural objects in these books.

Though we live in different worlds, Sister Margaret and I share a similar undertaking in creating our personal psalters. As Henrike Lähnemann observes, ‘Writing your own devotional manuscript is the perfect way to combine working and praying – the two key activities in monastic life.’ Copying each word by hand forces me to slow down, focus on the text, and meditate on it. The physical act of writing helps fasten ideas in my mind in ways that typing or even highlighting cannot. I find myself pausing mid-line, connecting the text with events around me, or feelings within me, and offering them in lament or gratitude.

In his essay ‘On Fairy Stories’, J.R.R. Tolkien writes on what he calls sub-creation. ‘We make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.’ In designing and creating our own psalters, both Margaret and I are imitating a Creator who made the earth and its inhabitants. Medieval people sometimes depict God as a divine artist, dividers in hand (as in a Bible moralisée, MS. Bodl. 270b, fol. 1v). This mindset also portrays God as enabling humans to participate in his handiwork, and to fashion our own works of art. The creative process is therefore a kind of transcendence, a welcome opportunity to escape the chaos of today’s politics and plague, and connect with things that are valuable and eternal.