Inside the wooden upper-board of one of the Bodleian Library’s 12th century manuscript hides what is perhaps a guilty secret. A mysterious pattern of lines, etched in to its surface.

Every few weeks since the beginning of this digitization project I have accompanied curator Matthew Holford, as we weave our way through the maze of shelving units which make up the Bodleian’s underground book stack. As one of the photographers tasked with producing images for this project, it has been helpful to periodically assess the next selection of manuscripts, before their delivery to the studio. This process has enabled us to separate volumes which may need to be referred to our conservators prior to digitization, and to identify volumes which may require specific attention during photography. Carefully removing each of these manuscripts from their protective boxes never fails to excite and surprise, and it’s during one of these assessments that I first glimpsed the strange etched pattern tucked away inside MS. Lat. liturg. d. 38.

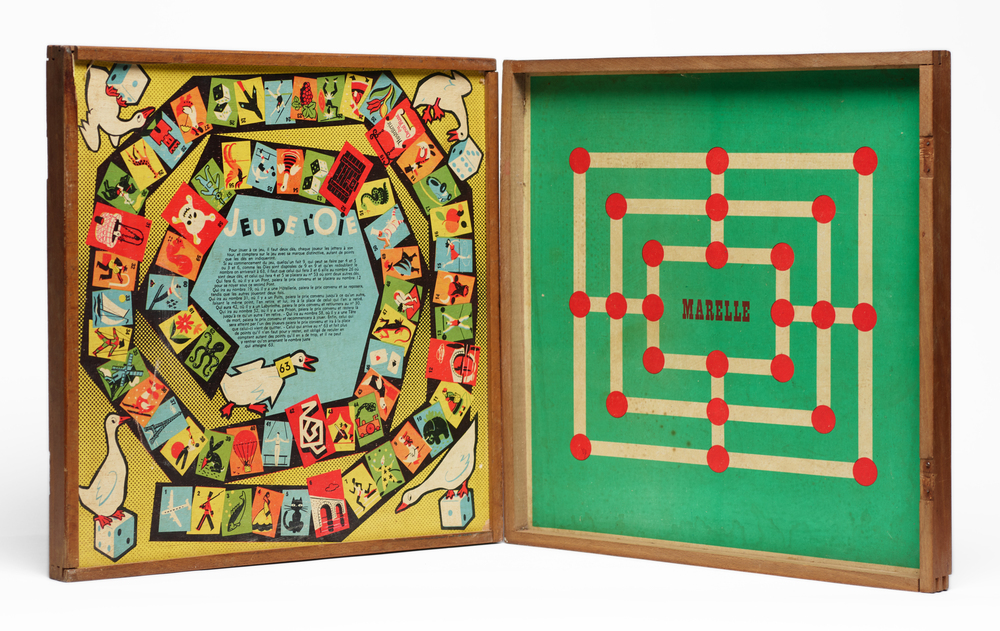

As a keen player and collector of abstract strategy board games, the incised lines carved into the board of MS. Lat. liturg. d. 38 were immediately recognisable to me. Though the manuscript is certainly not a work describing the rules of medieval games, it’s clear that these etched lines form the game Nine Men’s Morris, otherwise known as Mill, Mühle, or Merelles. In fact, this mid-12th century manuscript is a liturgical psalter and calendar. One can imagine the game might perhaps have provided a distraction from study for many readers during the intervening centuries.

Even when this manuscript was made, Nine Men’s Morris would have been considered an ancient game, dating at least to the Roman Empire, though it would have remained popular in medieval Europe.

In 2013, I had the good fortune of photographing MS. Bodley 264, an exceptionally beautiful 14th century Flemish manuscript of the Romance of Alexander and Marco Polo, the borders of which contain wonderfully painted and illuminated illustrations depicting everyday medieval life. At the bottom of one of its pages, a couple on the right are shown playing a game of Nine Mens Morris next to another, on the left playing chess.

Bodleian Library MS. Bodley 264, fol. 112r. Nine Men’s Morris being played in lower-right illustration

Naively, I had hoped that I might be the first to shine a light on the purpose of the etched upper-board board of MS. Lat. liturg. d. 38, but of course the Bodleian’s knowledgeable curators had beaten me to it, making reference to the game in the medieval.bodleian catalogue.

This is just one example of the fascinating, mysterious and beautiful manuscripts which my colleagues; David Mitchell, David Belcher, Nick Emm and I have photographed since May 2018 for the Manuscripts from German-Speaking Lands project. Together, we have reached a new project milestone, having completed the photography of the 300th volume. In total, we have photographed over 115,000 images to date, all of which will be made freely available to view on this website and on Digital Bodleian.

This is the Bodleian’s third Polonsky Foundation funded digitization project. Since 2013, my colleagues and I have photographed many hundreds of volumes from our Greek, Latin, Early Printed and Hebrew collections. With each new project, advances in technology and experience have enabled us to produce images of increasing quality and consistency. The images captured for Manuscripts from German-Speaking Lands are of the highest accuracy the Library’s Imaging Studio have produced for a large digitization project, and in many regards, this has been a project of firsts for the Bodleian.

It’s the first time that we have provided images of the bindings of each manuscript from every angle. Images of the upper-board, lower-board, spine, fore-edge, upper-edge and lower-edge are provided for all volumes.

It’s the first time that a project of this scale has been photographed exclusively using high resolution medium format camera sensors, with images captured at up to 100-million-pixels. This has enabled readers to zoom in to the very smallest marginal text, which may previously have been unreadable in a lower resolution digital image, or perhaps even when viewing the original manuscript.

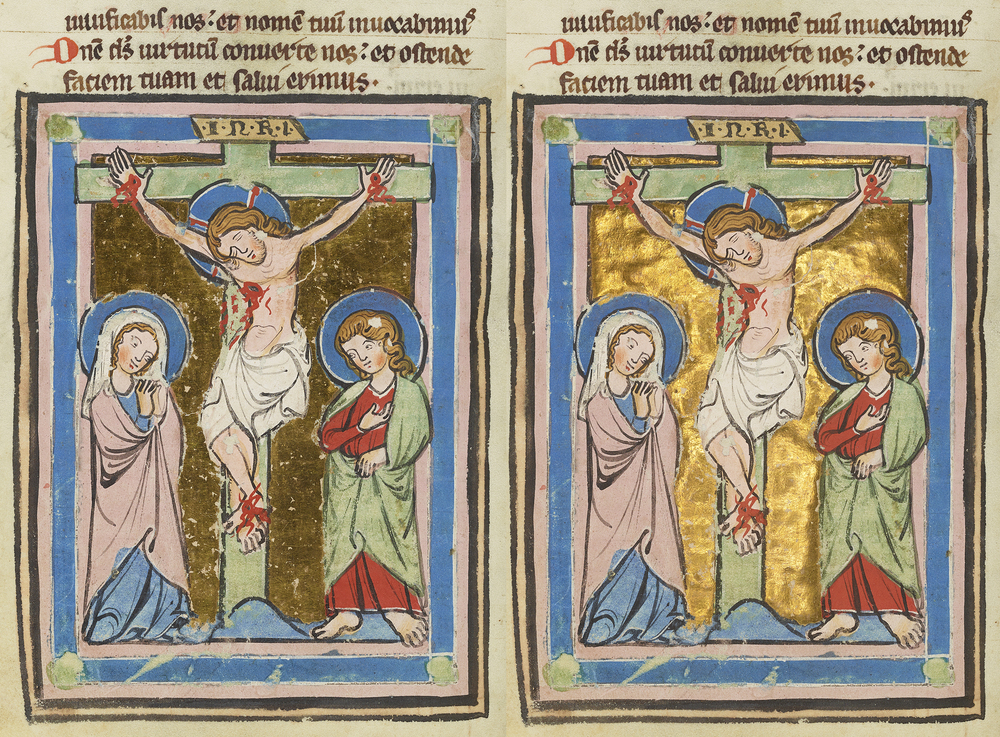

It’s the first time that we have used additional direct lighting for all manuscripts which contain illuminations. This is a technique which I have been developing since 2013. In addition to conventional lighting, a digitally controlled ring flash is used, near to, or surrounding the camera lens. This low power light source positioned parallel to the original, allows illuminations to be reflected back to the lens making it possible to correctly capture the colour and lustre of the gold leaf.

The technique was used to good effect when photographing the title-pages of the four Gospels found in MS. Canon Bib Lat. 60. In my fifteen years working for the Bodleian, I don’t think that I’ve seen a more beautifully decorated manuscript.

Bodleian Library MS Canon Bib. Lat. 60, fol. 48v

It is also the first time that we’ve included an object level, technical target in every image. This small card placed next to the millimetre scale at the fore-edge of each page contains six coloured patches and six greyscale patches and helps to ensure the colour and exposure accuracy of our images. We hope that by recording the tones and colours of the paper, parchment and pigments of our manuscripts faithfully, that this will provide a benefit to the users of our digital collections in their research.

During the course of this project, the Bodleian commissioned an Imaging Standards project in order to review the quality of the digital images which we produce, and to check for compliance with the two most widely used Guidelines for digitization. This has aided us in making additional adjustments and developing a workflow which is now being used in our imaging studio to create images which are compliant at the highest performance levels. Our aim is to provide the end-user with an experience which is as similar to having the physical manuscript in front of them as is possible.

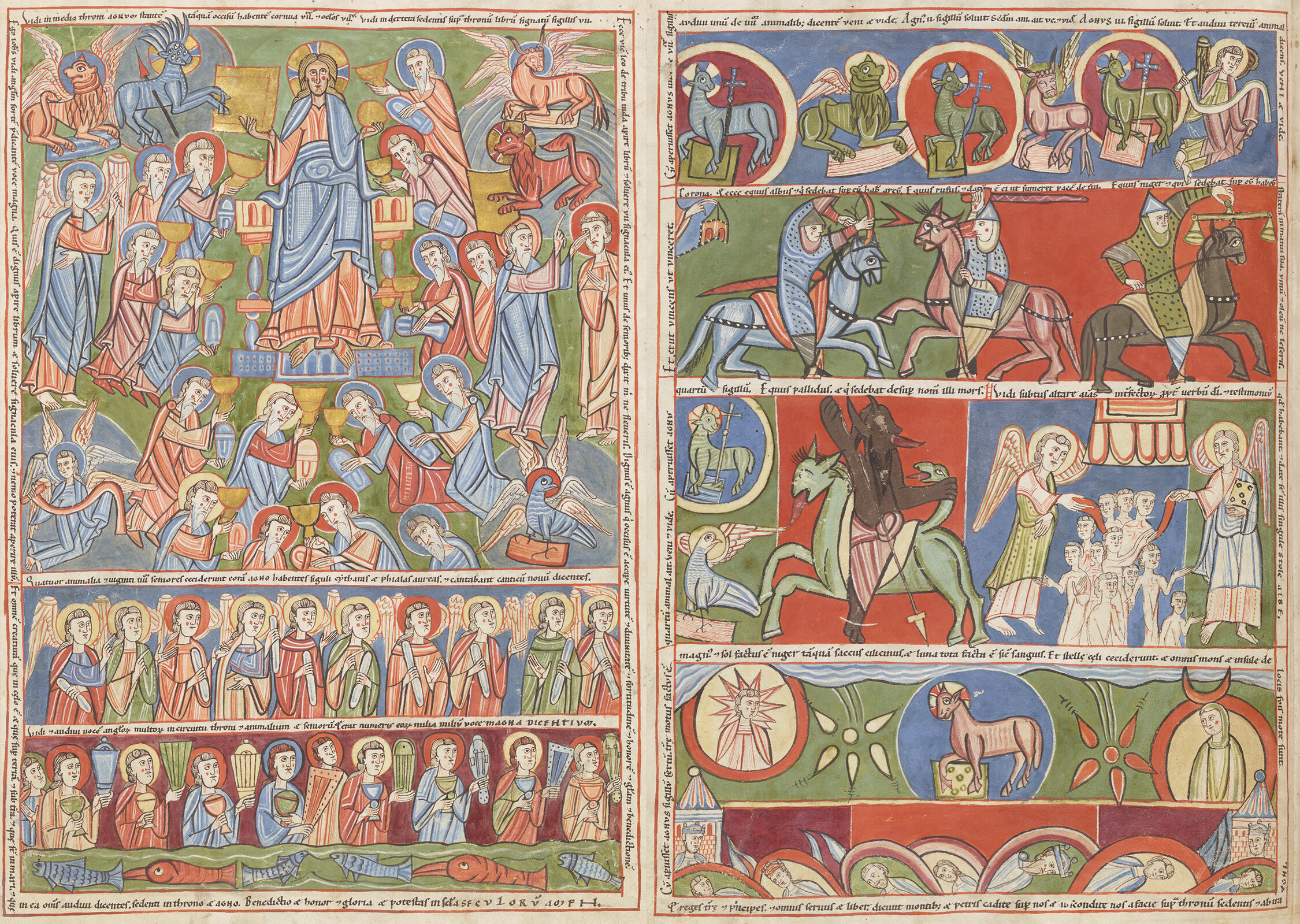

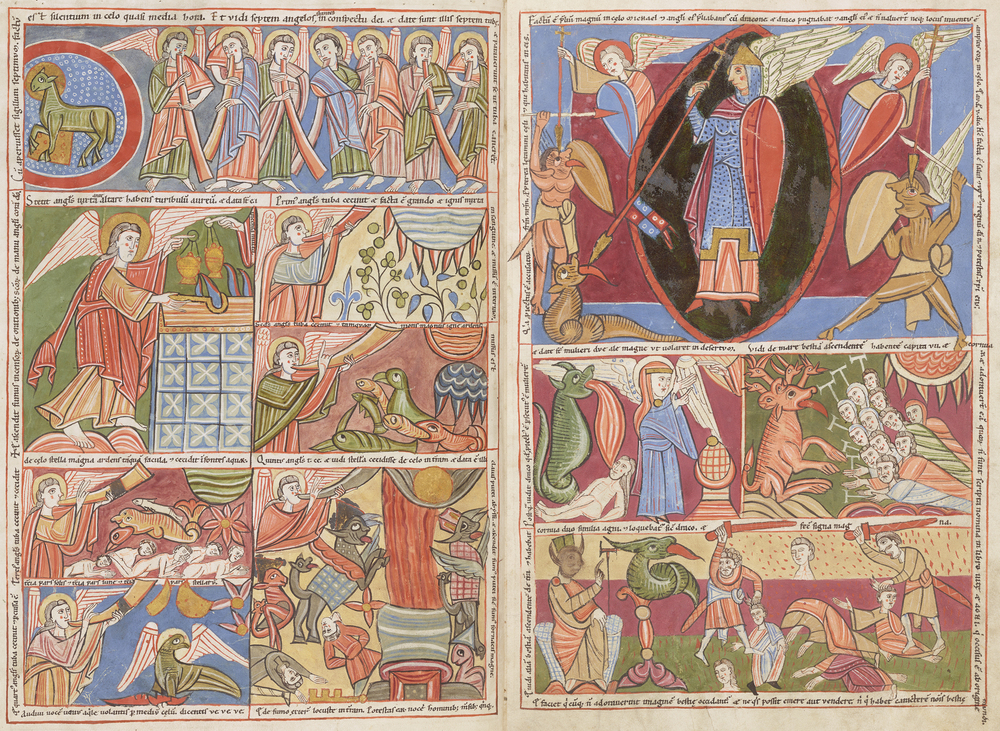

The 300th manuscript photographed for this project is MS. Bodl. 352; a 12th century illuminated Apocalypse. Although the colours in this volume are not as vibrant as others that I’ve photographed for the project, the illustrations are particularly unusual and as should be expected in an Apocalypse, often disturbing, but with a great deal of character. The opening section of this volume contains twenty beautifully painted folios. Each parchment page is entirely filled with illustrations of people, animals, fish and birds, often with gold-leaf illuminations. It’s rewarding to know that this volume and the 299 manuscripts preceding it, have now been photographed in their entirety, and for the first time will be available for all to enjoy online.

In a year where restrictions have made it difficult or even impossible to have the opportunity to view our collections physically, we have continued to work towards providing our readers the next best thing: high-quality digital facsimiles. digitization has never been so important.

John Barrett is a photographer in Bodleian Imaging Services.