What did twelfth-century monks have in common with twentieth-century artists? Monochrome art offers one connection between Cistercian monks and artists such as Kasimir Malevich or Yves Klein. Malevich’s Black Square was a key work in the development of abstract, non-representational art. The Cistercians’ reaction against the colourful and elaborate representational art of their contemporaries offers intriguing parallels.

The Cistercian order began around the turn of the twelfth century as an attempt to recover the original simplicity of the monastic life, particularly as codified in the Rule of St Benedict. Cistercian apologists contrasted their own austerity with the extravagances of Cluniac monks, who had deviated (in the Cistercians’ view) from the original rigour of the rule. This austerity was not only a question of diet, clothing, manual labour and liturgical observance but extended to the artistic sphere. Bernard of Clairvaux’s Apologia to William of St-Thierry (1124-1125), for example, famously inveighed against the ‘deformed beauty’ of cloister sculpture. Such lavish decoration was unnecessary, wasteful, and a distraction from devotion.

These attitudes were also codified in Cistercian legislation. The Cistercians have been described as the first true monastic order, because they were the first to establish a constitutional structure which united different houses in an organizational framework, with a general chapter meeting annually at Citeaux and - at least in theory - uniform observance throughout the order. By 1152 the order had issued statutes banning sculptures and pictures (except for crucifixes) and stating that in manuscript decoration, ‘letters should be of one colour, and should not be figurative (depicte)’. In 1202 this was repeated and elaborated: ‘letters should be completely non-figurative (absque omni…imagine) and without gold or silver’.

Some of the earliest Cistercian manuscripts had, in fact, been lavishly decorated. A famous example written and decorated at Citeaux around 1111 is a copy of Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job (now Dijon, BM, MS. 173). It seems that while the early Cistercians vigorously objected to elaborate liturgical ornaments, and also to elaborate bindings on books, the extension of these principles to manuscript decoration occurred later. By the middle of the twelfth century, though, decoration at Citeaux was dominated by what art historians have called the ‘monochrome’ style. A famous example is the ‘Grande Bible de Clairvaux’ (Troyes, BM, MS. 27). Wider studies of Cistercian manuscript art have found that the statutes were not observed with uniform rigour. Nevertheless, all Cistercian monasteries did tend to avoid miniatures, figurative initials and the use of precious metals in the manuscripts they produced. While their decorative initials were not always - indeed not often - fully monochrome, they were usually restricted to a limited palette, often using only one contrast colour.

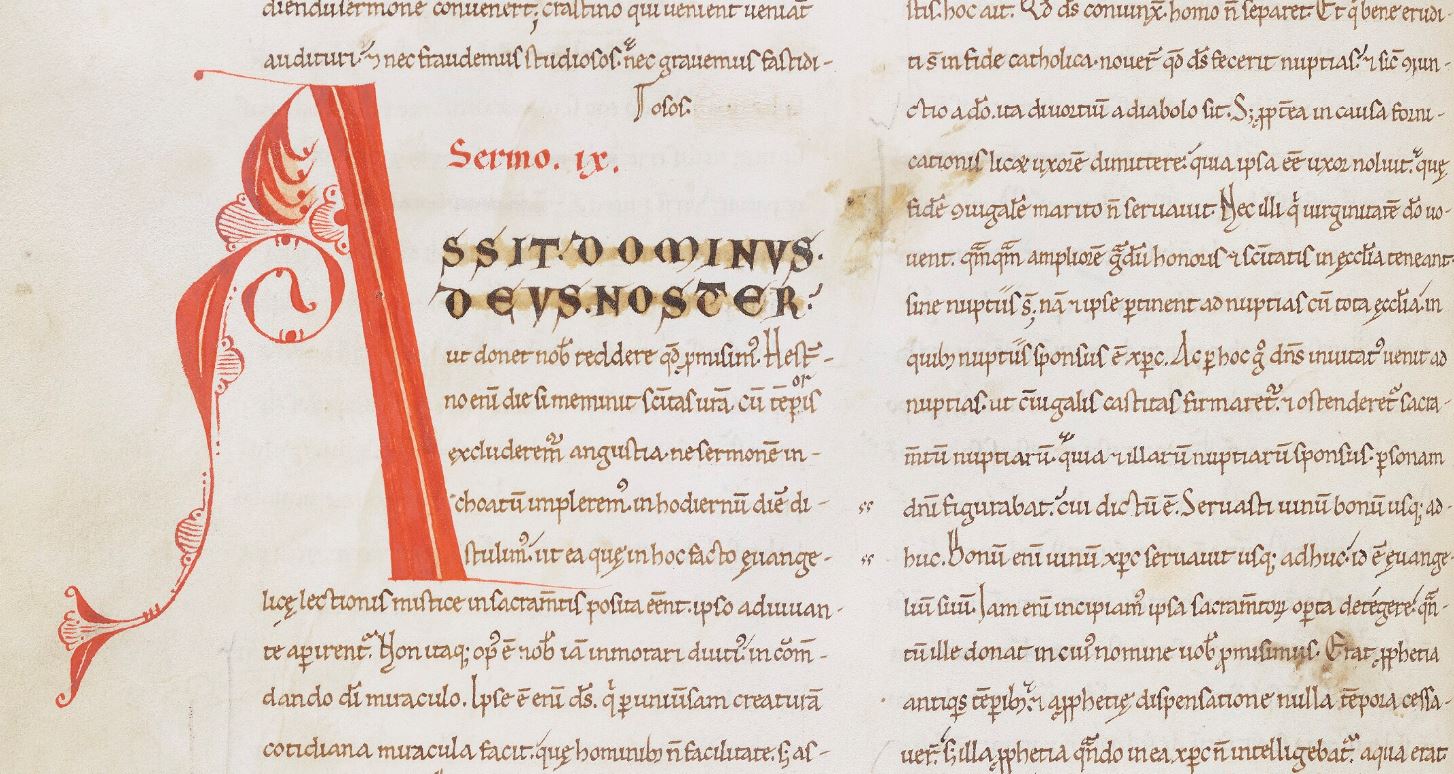

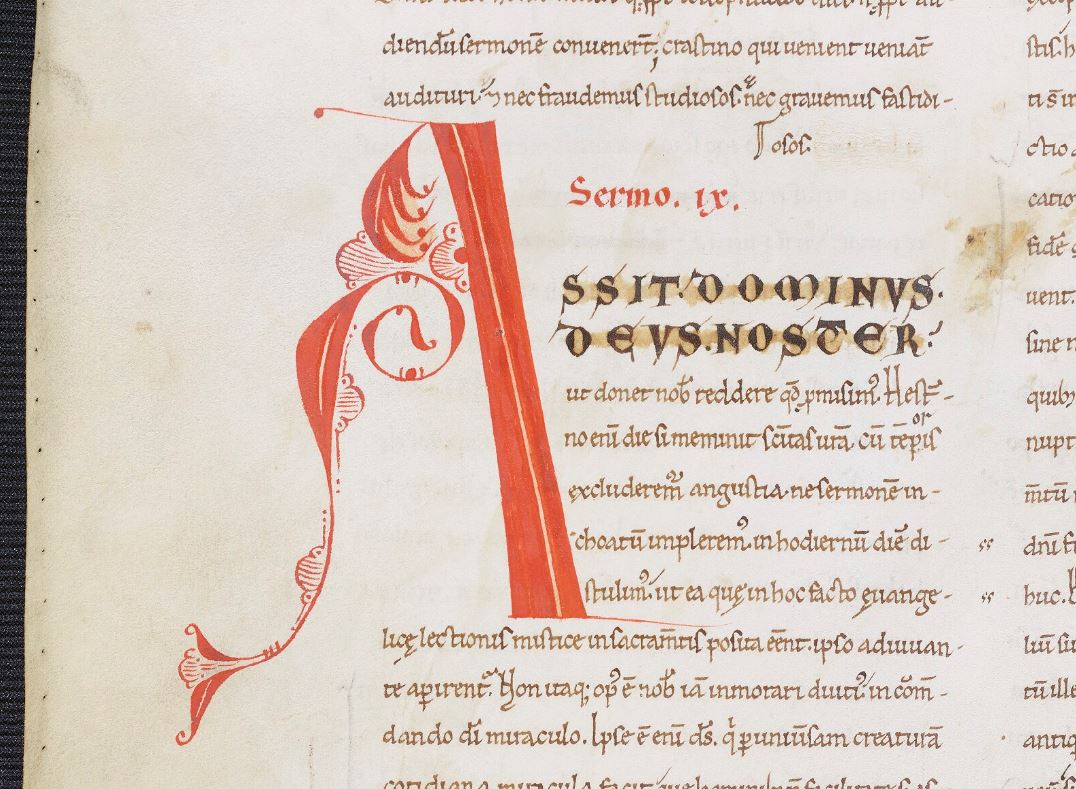

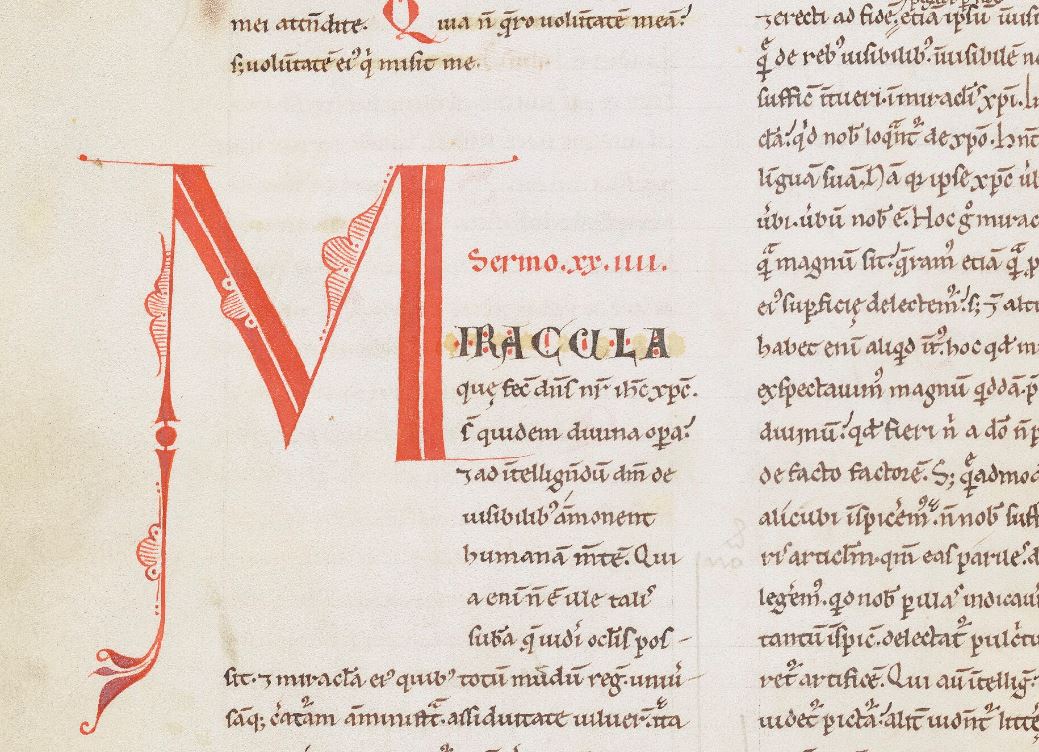

The manuscripts written at Eberbach, such as Bodleian MS. Laud Misc. 144, in fact conform to the stricter end of the Cistercian spectrum. As Nigel Palmer has pointed out, the twelfth-century manuscripts contain no miniatures, and only one historiated initial. Many initials are plain red; those that are decorative tend to be monochrome, usually red, sometimes with yellow highlighting. The decoration is entirely non-figurative, consisting of abstract, geometrical or foliate patterns. They fulfill their function of articulating the divisions of the text without distracting from its content.

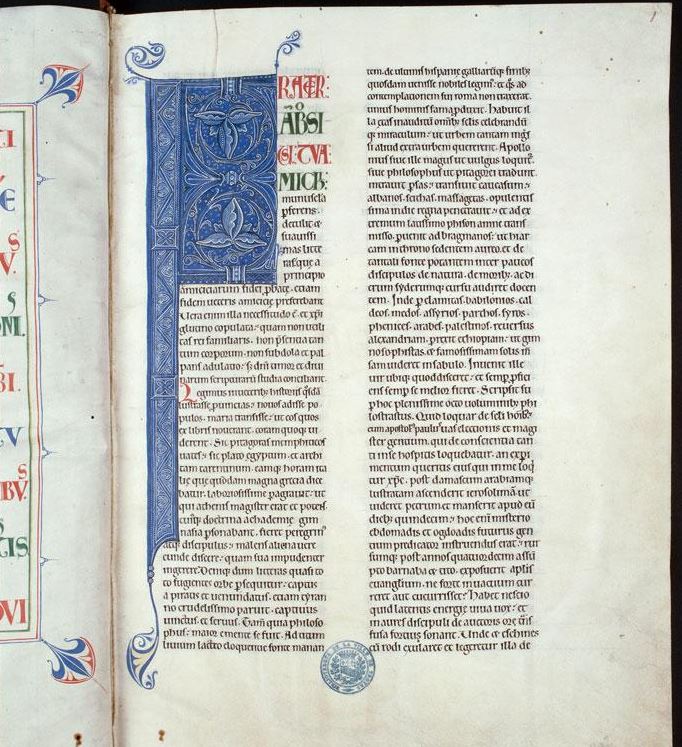

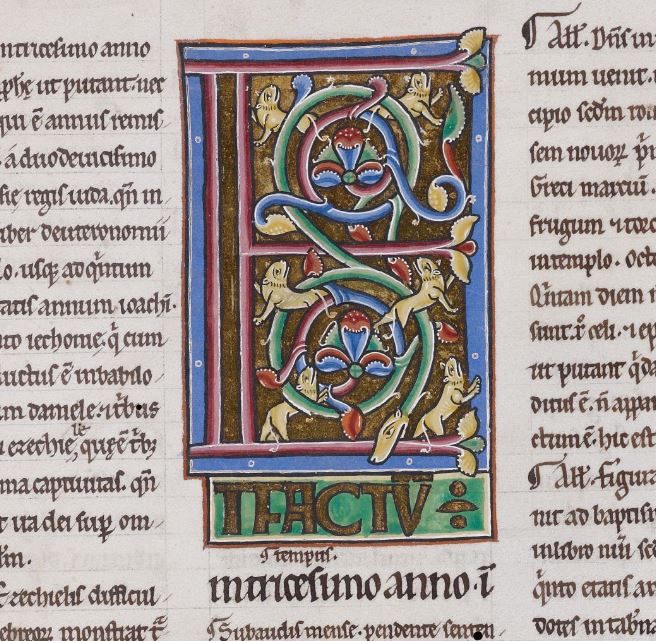

These principles did not apply to all the manuscripts in the Eberbach library, however. As at other Cistercian houses, exceptions were made for manuscripts brought to the abbey from elsewhere. A glossed Bible from Paris, with its multicoloured initial on gold ground containing animal figures (MS. Laud Misc 102, fol. 184r), provides a striking contrast to manuscripts decorated in the abbey itself.

Books written for export may also have been excepted. This may explain the elaborate initial with gold ground in the Exordium magnum Cisterciense (Bodleian MS. Laud Misc. 238), which Palmer has suggested was produced for a nunnery dependent on Eberbach.

MS. Laud Misc. 238, fol. 7r, initial E.

The Cistercian enthusiasm for simplicity sometimes tended to wane in the later middle ages. How far this was true of manuscript decoration at different institutions, however, deserves more study. At Eberbach decoration seems to have remained sober throughout the middle ages. Kasimir Malevich might have approved.

Further reading

For an introduction to the Cistercians see The Cambridge Companion to the Cistercian Order, ed. M. B. Bruun (2012), with a chapter on art by Dianne Reilly. For Cistercian legislation on art and its interpretation see A. Lawrence-Mathers, ‘Cistercian decoration: twelfth-century legislation on illumination and its interpretation in England’, Reading Medieval Studies, XX (1995), 31-52. Manuscript decoration at Citeaux is discussed by Y. Załuska, L’Enluminure et le scriptorium de Cîteaux au XIIe siècle (1989). For Eberbach see N. Palmer, Zisterzienser und ihre Bücher (1998), esp. pp. 70-80, 86.

Matthew Holford is the Tolkien Curator of Western Medieval Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library.