Digitization projects are not just about sharing with the world what we already know and love about our collections. Creating and updating metadata - catalogue descriptions and image metadata - gives us a chance to look again at our manuscripts and - sometimes - make new discoveries. The Eberbach manuscripts, which have not been described in detail since the mid-nineteenth century, will be a particularly fertile hunting ground, and one significant discovery has already come to light in MS. Laud Lat. 97, a selection of Old Testament books which was not written at Eberbach but came to the abbey perhaps by the late twelfth century and certainly by the fifteenth.

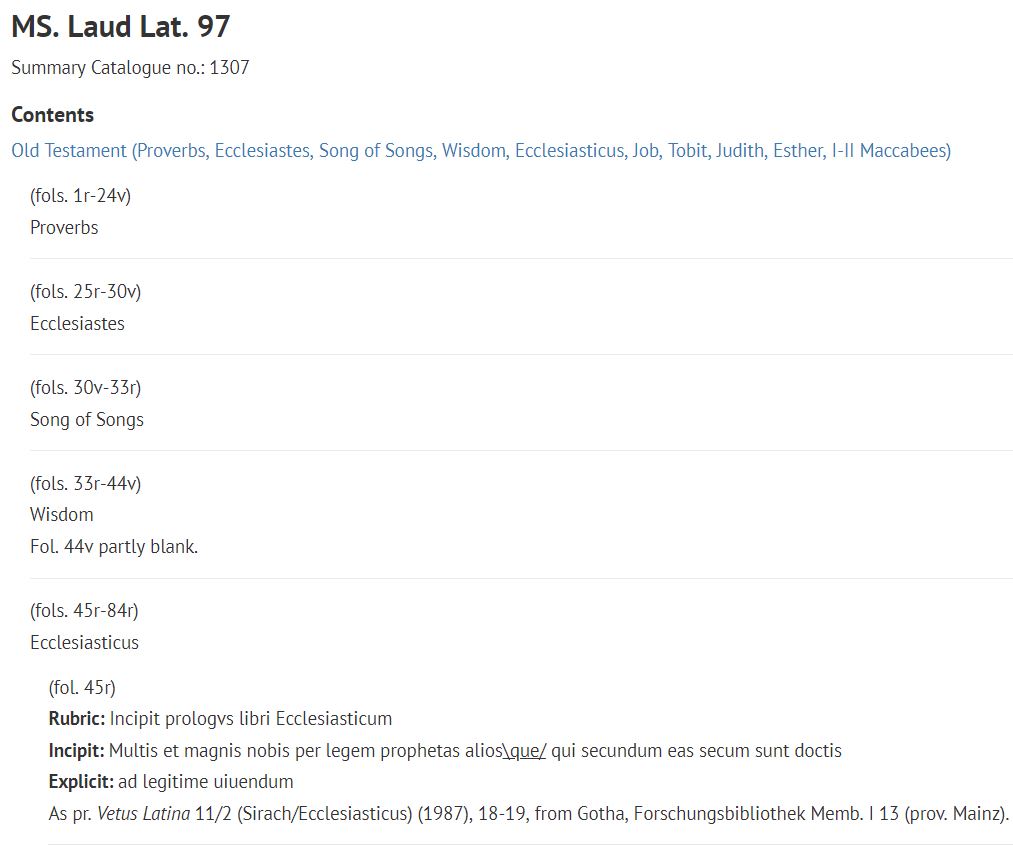

Cataloguing resources are limited (more on this in a future post), but we aim to review existing descriptions to ensure they are accurate and that they provide an adequate guide to the key features of a manuscript. One key objective is to facilitate navigation of the digitized images using the ‘index’ feature of the Universal Viewer. The existing descriptions of MS. Laud Lat. 97, which did not indicate where the different biblical books were to be found, and described the prologues only generally, were not helpful in this respect, so a new description of the contents was created. It was at this point that the unusual prologue came to light. Although the nineteenth-century catalogue stated or implied that all the biblical books were accompanied (as often) by the prologues written by Jerome, this was misleading; some books have no prologues, while Ecclesiasticus (the deuterocanonical book also known as Sirach or Ben Sira) has two. It is the first of these, beginning ‘Multis et magnis nobis per legem’, that is of particular interest.

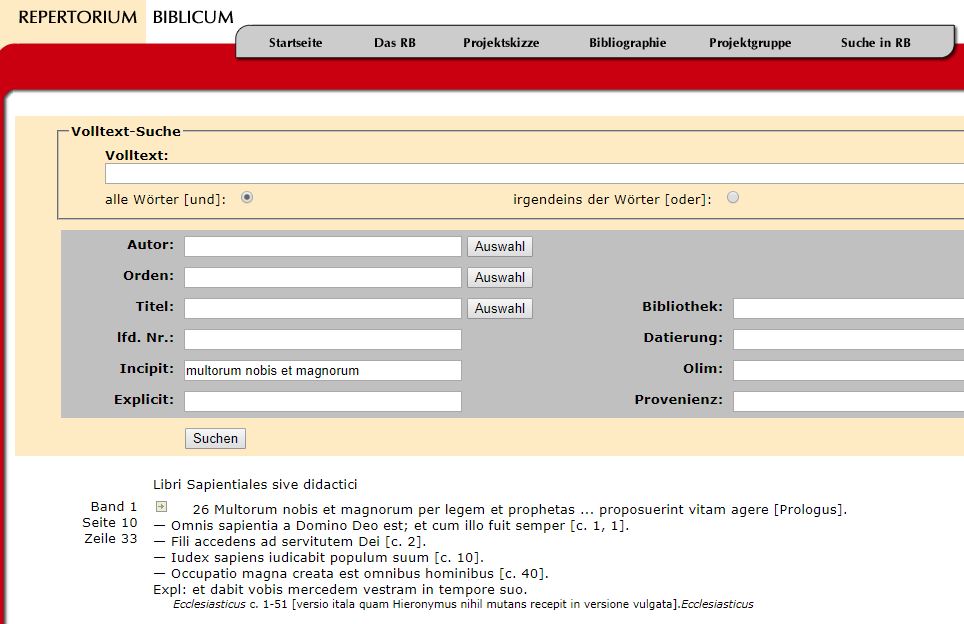

There are several fundamental reference works which cataloguers use to help identify texts. For manuscripts of the Bible the most important is the Repertorium Biblicum of Friedrich Stegmüller, now available online. This contains the usual prologue to Ecclesiasticus, beginning ‘Multorum nobis et magnorum’ (entry 26) but not a prologue beginning ‘multis et magnis’. Another very helpful resource is the subscription database In principio, which collects information about the incipits (opening words) of a large number of texts. This too contains the usual prologue to Ecclesiasticus but not the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue. The cataloguer’s next point of call (it may even have been their first) is likely to be Google (other search engines are available), since the exponential increase in the digitization of books means that a web search is often as likely to lead to an identification as a traditional reference work or database. And a search for the phrase ‘Multis et magnis nobis per legem’ will indeed lead to the printed text of the Vetus Latina (the ‘old Latin’ translation of the Bible which preceded Jerome’s Vulgate translation), which will provide the main source of information about this text. From the Vetus Latina we learn that the text of the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue was first printed by dom. Donatien de Bruyne in 1929. De Bruyne had discovered text in Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, Memb. I 13 (fol. 104v), a late-twelfth-century manuscript which belonged to Mainz Cathedral. The Gotha text was also discussed in the edition of the Greek Septuagint text by Joseph Ziegler (1965) and printed again by Walter Thiele in 1987 for the Vetus Latina.

The Gotha manuscript was the only manuscript known to all scholars , and from it they reached quite different conclusions. De Bruyne and Thiele agreed that the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue represented a more literal translation of the Greek original, in comparison to the standard prologue. They agreed that it was missing some text (between the words ‘congruens est’ and ‘disciplinatus’), probably because the scribe had skipped over a passage. Thiele in addition pointed out that the Gotha text contained misunderstandings of the Greek. (Most notably the personal name Ευεργετος (Ptolemy Euergetes) was misunderstood.) Both also pointed to places where the text was corrupt and needed emendation to make sense. The manuscript text ‘secum sunt doctis’, for example, needs to be emended to read ‘secuti sunt datis’.

However, de Bruyne, Ziegler and Thiele reached very different conclusions about the date when the second prologue was originally written. De Bruyne believed that both versions of the prologue were independent, early attempts to translate the Greek text into Latin. Ziegler rejected this suggestion, arguing that the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue was a later correction of the original prologue, and should be associated with early manuscripts of the Latin text that had been corrected with reference to the Greek. Thiele, on the other hand, saw no reason to think that the Gotha text was earlier than the manuscript itself, or that it had any wider circulation. He implied, that is, that the translation was carried out in twelfth-century Germany.

MS. Laud Lat. 97, fol. 45r: prologue beginning ‘Multis et magnus nobis ler legem’

The significance of the newly-discovered text in MS. Laud Lat. 97 will not be fully apparent until the text has been edited and the manuscript’s date and origin fully reassessed. (Previous cataloguers have localized it to Western Germany and dated it to either the first half of the twelfth century (Pächt and Alexander) or the second half of the eleventh (Palmer).) The newly-discovered text shows that Thiele was mistaken, at least in some respects, since the prologue did have something of a wider circulation, even if only in the Mainz area. Closer comparison of the Laud and Gotha texts indicates that they are related, but that neither was derived from the other, meaning that we must posit at least one other lost manuscript from which they derive. Like the Gotha manuscript, the Laud text has the lacuna ‘congruens est † disciplinatus’ at the beginning and it shares the corrupt text ‘secum sunt doctis’. In some cases Laud provides a better reading, as with ‘discendi’ for ‘descendi’ (l. 10), or ‘lectionem’ for ‘lictionem’ (l. 18). In other cases Gotha has the better text, as with ‘adtentionem’ for ‘attentiorem’ (l. 29).

It is quite possible that other copies of the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue await discovery in medieval bibles whose contents have not been fully catalogued. Even on the basis of the two copies currently known, however, we can tentatively speculate that this prologue goes back earlier than the twelfth century. The nature of the copying errors found in both manuscripts is suggestive. The confusion in both Gotha and Laud of ‘a’ and ‘oc’ (‘doctis’ for ‘datis’) suggests an earlier source using ‘oc’ shaped a, while the confusion of ‘n’ and ‘r’ in Laud (‘adtentionem’ for ‘attentiorem’) may suggest an insular r, easily confused with n. The reading ‘secum’ for ‘secuti’ perhaps also suggests misunderstanding of an insular ‘ti’ ligature. Taken together these errors may suggest that the ‘multis et magnis’ prologue was transmitted at some stage in insular minuscule and was therefore circulating in or before the ninth century.

References

- Donatine de Bruyne, ‘Le prologue, le titre et la finale de l’Ecclesiastique’, Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 47/1 (1929), 257-63 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1929.47.1.257

- Sapientia Iesu filii Sirach, ed. Joseph Ziegler (Göttingen, 1965)

- Vetus Latina 11/2: Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), ed. Walter Thiele (Freiburg, 1987), esp. 16-19

Matthew Holford is the Tolkien Curator of Western Medieval Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library.