It’s been a little over a year since we began project photography in earnest here at the Bodleian, and a little under a year since the first items went online. Time enough to look at the 80-odd manuscripts we’ve completed so far, and ask: what have we digitized?

One of the organising principles of our Collection in this project is the provenance of the manuscripts - chiefly, which German religious house the manuscripts were associated with. While we’ve digitized manuscripts from 10 separate houses (plus a few of uncertain origin), between them, the Cathedral Church (Domstift) of St Killian in Würzburg and the Cistercian Abbey of the Virgin Mary in Eberbach account of almost all the Bodleian items completed to date.

This is in part a result of a later step in the provenance of our manuscripts: the donations through which they arrived at the Bodleian. Many of our German manuscripts are shelfmarked “MS. Laud…”, indicating that they were given to the Library by William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor of the University in the 1630s. Laud’s agents purchased groups of manuscripts dispersed from the religious houses which had held them in the upheavals of the Thirty Years War, most of which had belonged to either the Domstift St Kilian, Eberbach abbey, or the Charterhouse in Mainz.

The other reason our progress so far is skewed towards Wurzburg and Eberbach manuscripts - and the reason Mainz has yet to put in an appearance - is to do with how we’re organising our work in this project. As part of putting the manuscripts online, we’re updating their records in our dedicated Medieval Manuscripts at Oxford TEI catalogue. This is done with reference to existing print catalogues, several of which describe manuscripts held by specific houses. This year our efforts were concentrated on manuscripts featuring in Daniela Mairhofer’s Medieval Manuscripts from Würzburg in the Bodleian Library, Oxford: A Descriptive Catalogue (Oxford, 2014) and Nigel Palmer’s Zisterzienser und ihre Bücher: die mittelalterliche Bibliotheksgeschichte von Kloster Eberbach im Rheingau (Regensburg, 1998) - our warm thanks again to both for permitting us to use their work in this project.

As we move into our second year, you’ll also see more manuscripts previously held by religious institutions in Erfurt appearing online. These are from the group of around a hundred manuscripts given to the Bodleian by the sons of Sir William Hamilton after his death in 1856.

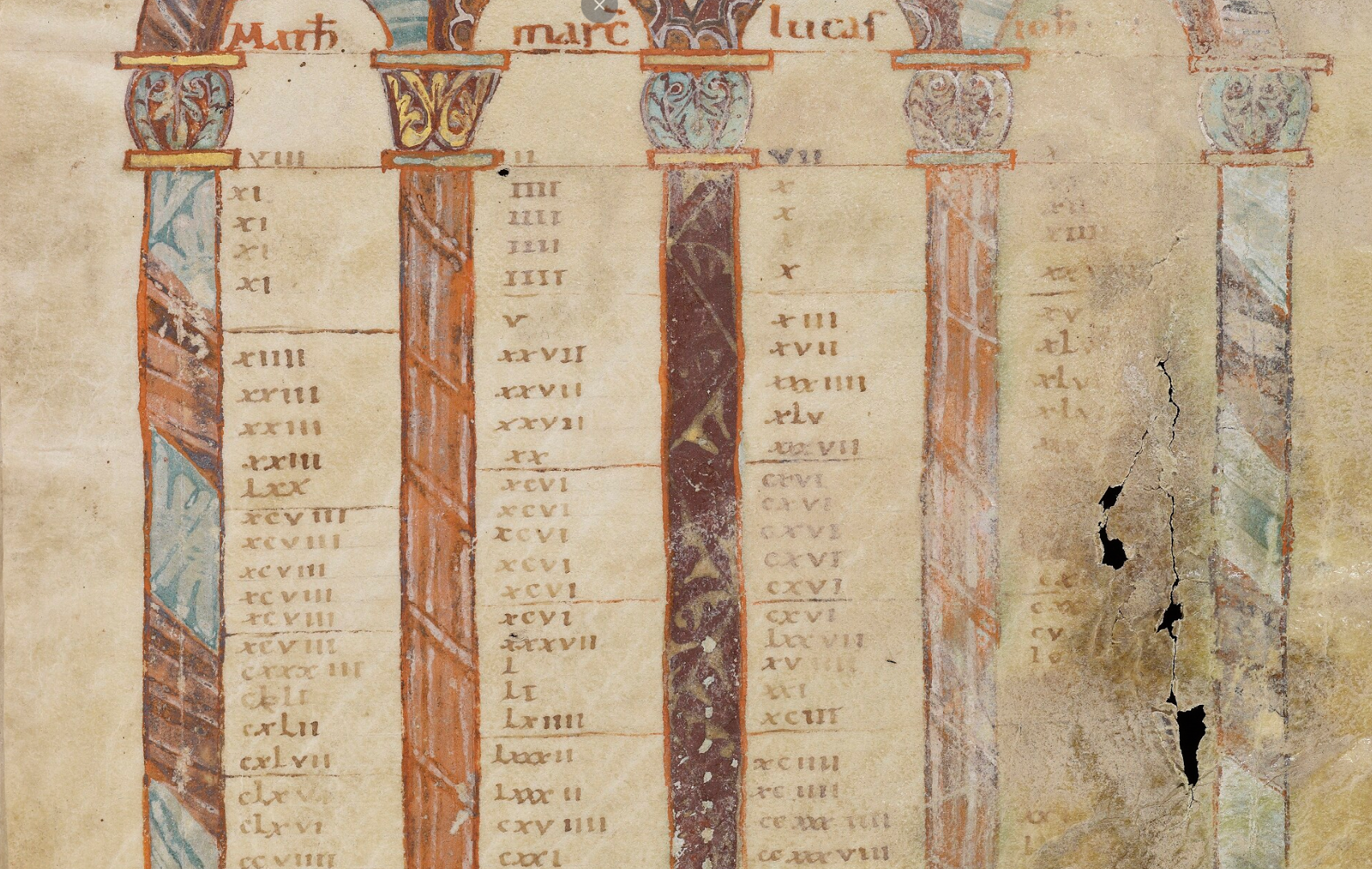

The collection histories of the digitized manuscripts also help account for the dates of the works digitized so far. We’ve digitized manuscripts dating from the mid-8th to the early 16th centuries, but 9th century and 12th-13th century items predominate. The 9th century manuscripts are almost all from the holdings of the Domstift Wurzburg, which was established by St Boniface in 741 or 742, and probably had its own scriptorium by the end of the century. That mid-8th century manuscript, MS. Laud Misc. 126, in fact contains a later selective booklist of items held in Wurzburg in the 9th century.

The other extended peak represents manuscripts produced in the later 12th and earlier 13th centuries, mostly held by the Cistercian Abbey of Eberbach. The abbey was re-founded in the 1130s, and by the end of the 12th century had received a new church building, founded several daughter-houses, and established a scriptorium.

Matthew Holford wrote last year about the austere decoration expected of Cistercian texts, and it’s true that the manuscripts in this project are not a flashy bunch - Cistercian or otherwise. Miniatures do not feature (much), though we have a few inhabited initials, elaborate initial pages, and other examples of impressive decoration. The remaining texts are more restrained - though we dare anyone to say the fine Carolingian and protogothic scripts represented in this project aren’t among the most handsome in the Library.

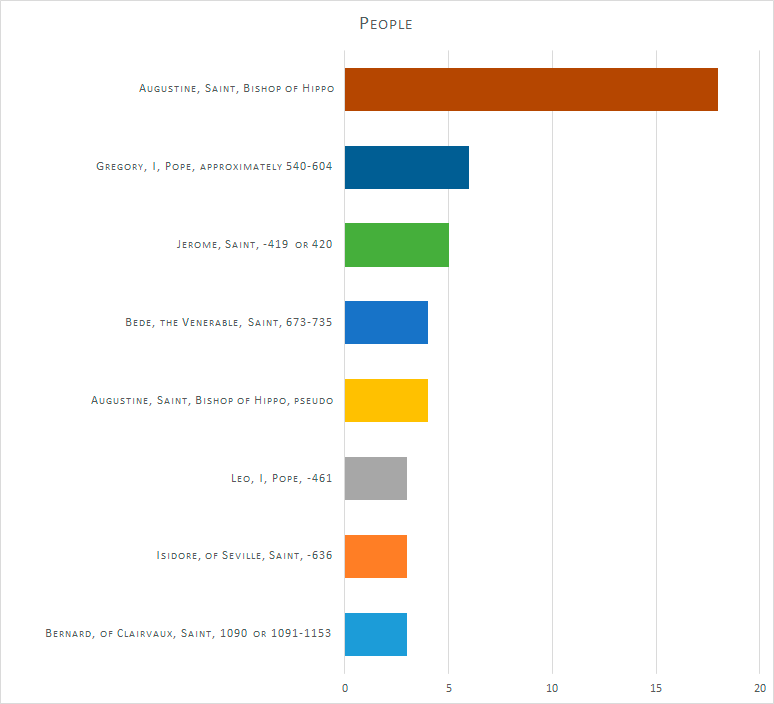

The texts themselves are highly varied, and a crude distribution into broad genres shows the spread. Biblical books, commentaries thereon, sermons, homiliaries and other liturgical texts of many stripes feature, as do more broadly theological or philosophical treatises.

Augustine is especially well represented, featuring in a whopping 18 different digitized manuscripts (nearly a quarter of those we’ve digitized so far), with pseudo-Augustinian texts also featuring in four manuscripts.

Gregory the Great, St Jerome, Bede, Isidore of Seville, Leo the Great and Bernard of Clairvaux all also feature in more than two manuscripts.

The coming year will bring scores more items from our collection online. We’re still not finished with the Laudian manuscripts, and we’ve most of the Hamilton group still to come, as well as individual manuscripts of Germanic origin from our wider holdings. Expect to see a few more manuscripts from smaller houses, and a slight evening out of the date distribution of our digitized items; much of the Hamilton collection is later medieval in origin. Other trends will likely continue - we’ll be surprised if Augustine is knocked off the top spot of most-represented-author.

Tim Dungate is the Bodleian’s Assistant Digital Curator.